Coping with change in a warming Mediterranean

More frequent and intense droughts, storms and heat waves, melting glaciers, warming oceans and rising sea levels – climate change is already causing immense harm to the natural world, putting countless species, including our own, at risk.

WWF’s ‘How climate changes wildlife’ series focuses on the need to safeguard wildlife around the world from these harmful impacts. In this second feature, we look at how warming waters are changing ecosystems in the Mediterranean Sea – and how we’re helping people and wildlife to respond.

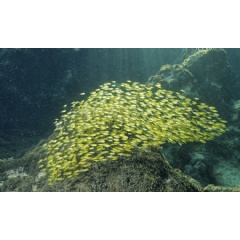

Since the dawn of civilization, people have depended on the Mediterranean Sea and its natural riches. Though it makes up less than 1 per cent of the world’s ocean, it’s home to 10 per cent of all known marine species – from whales, dolphins and porpoises, to loggerhead and green turtles, to more than 80 species of sharks and rays.

More than a quarter of the Mediterranean’s species don’t exist anywhere else.

But the Med is in trouble. Its incredible biodiversity is already under huge stress from overfishing, pollution and coastal development. And now climate change is ratcheting up the pressure.

Mauro Randone, WWF-Mediterranean Regional Projects Manager, says: “The Mediterranean is warming 20 per cent faster than the rest of the planet, and its ecosystems are already experiencing dramatic changes – with knock-on effects for fishing communities, tourism and people’s livelihoods.

“Invasive alien species are expanding their range, displacing native wildlife and damaging habitats. Other native species are shifting northwards to cooler waters, and some endemic species are now on the brink of extinction. Increasingly frequent and severe storms also threaten both coastal communities and fragile marine ecosystems like corals and seagrass.”

Nearly 1,000 invasive species, including 126 types of fish, have migrated into the Med from the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, mainly via the Suez Canal. Until recently, Mediterranean waters were too cold for most – but now many of them are thriving and spreading out to the north and west due to the warming impact of climate change.

Some of these alien species are having a devastating impact.

Rabbitfish, for example, which originally come from the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific, have colonized large stretches of the coast of Türkiye, where their ravenous grazing is turning complex seaweed habitats into barren rocky areas. One study in Greece and Türkiye found that areas with large numbers of rabbitfish had 40 per cent fewer species overall, and up to two-thirds less vegetation like large seaweeds.

Venomous lionfish are now well established across the southern and eastern parts of the Mediterranean, and have been found as far north as Italy.

Lionfish eat large numbers of small native fish and crustaceans, and have caused havoc in other parts of the world where they’ve been introduced. A recent study found that 95 per cent of lionfish’s prey in the Mediterranean was made up of ecologically and economically important native species.

While the Mediterranean’s alien invaders can be a threat to native species and fisheries, WWF and partners have been working with local fishers to help them respond.

For example, there has been action against an explosion in numbers of blue crabs, another species thriving in the warming waters of the southern Med after migrating from the Indo-Pacific. With a single female releasing up to 8 million eggs at a time, these aggressive and voracious predators have had a dire impact on the already limited fish stocks available to small-scale fishers.

But blue crabs make good eating themselves – and in Tunisia, WWF and partners have been training local fishers to target them. Crab fishing provides employment and income for local people, while keeping numbers under control.

And there are other benefits too, explains Mehdi Aissi, Marine Programme Manager for WWF North Africa, says: “With WWF support, the local community in the Gulf of Gabes has now embraced sustainable crab fishing but also, importantly, is targeting less endangered sharks and rays. Local fishers have also become strongly involved in conservation efforts, including creating a voluntary no-take zone and an artificial reef to rehabilitate a rich biodiversity area under pressure.”

Another example of how climate change is harming wildlife is what’s happening to Posidonia oceanica, a type of seagrass endemic to the Med. Around 2 million hectares of underwater Posidonia meadows along the Mediterranean coastline provide habitat for thousands of species, including vital nursery grounds for commercially important types of fish.

At the same time, they absorb and store vast amounts of carbon – equivalent to between 11 per cent and 42 per cent of all CO2 emitted by Mediterranean countries since the Industrial Revolution. And they help to shield coastlines from the impacts of climate change by slowing down waves and reducing erosion.

Yet warming waters, invasive algae and herbivorous fishes, and rising sea levels are all harming the health of seagrass meadows, undermining their ability to capture carbon and support climate resilience.

More than a third of the Med’s Posidonia meadows have been lost in the last 50 years, so we urgently need to look after the rest.

That’s why WWF is working across the region to protect 7.5% of the remaining Posidonia meadows by 2027. Working closely with local communities, governments, scientists and finance institutions, we’re piloting new solutions to tackle threats like boat anchoring (which can tear out Posidonia roots), illegal fishing and pollution.

WWF-Mediterranean’s Mauro Randone says: "Climate change is already fundamentally altering the Mediterranean Sea. But from supporting nature-based solutions, like protecting and restoring Posidonia meadows, and rebuilding stocks of key species that keep the ecosystem in balance, to finding innovative ways to adapt, like properly managing invasive species fisheries and promoting their overall consumption, we are helping people and biodiversity to cope with the impacts.”

See more:

WWF’s work on the climate crisis

Wildlife at WWF

WWF-Mediterranean

Beginning in Africa and journeying northwards to the Arctic, this four-part series – from April to August – examines how climate change is affecting wildlife.

Part 1: Deepening drought and the threat to iconic African elephants

Part 2: Coping with change in a warming Mediterranean

Parts 3 and 4: to be published in coming months

WWF is partnering with a pioneering public art project, called THE HERDS to inspire action for climate and nature. Until August 2025, herds of life-sized puppet animals are stampeding through city centres on a 20,000 km route from Africa’s Congo Basin to the Arctic Circle − an artistic representation of wildlife escaping life-threatening climate impacts that aims to inspire urgent action by people everywhere.

WWF Working to sustain the natural world for the benefit of people and nature

( Press Release Image: https://photos.webwire.com/prmedia/7/338371/338371-1.jpg )

WebWireID338371

This news content was configured by WebWire editorial staff. Linking is permitted.

News Release Distribution and Press Release Distribution Services Provided by WebWire.